FlowerMoundGrowth

Guidelines for Texas City Park Land Planning

An Analysis of Parkland Dedication Ordinances in Texas / Spring 2010

Journal of Park and Recreation Administration / Volume 28, Number 1

AUTHOR: John L. Crompton is with the Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences, Texas A&M University, , 2261 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843-2261; Phone 979-845-5320; Email: jcrompton@tamu.edu.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first detailed critique of parkland dedication ordinances to appear in the literature.

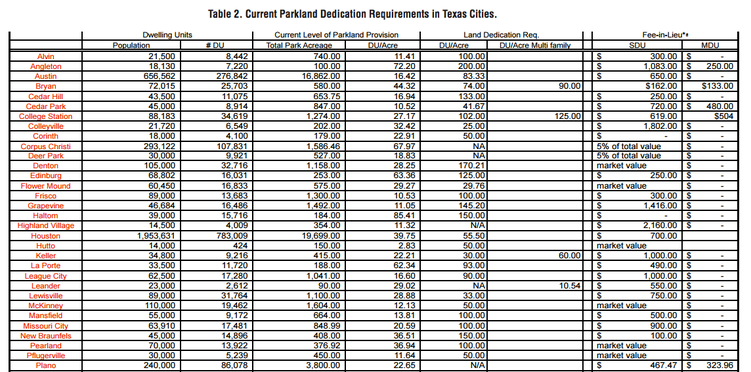

The purpose of this paper is to report on the present status of parkland dedication ordinances in Texas. A survey was sent to all municipalities in Texas that were known to have public park amenities.

"Clearly, it is advantageous for small cities that anticipate future growth to invest substantially in park areas in their early stages of development, because that investment could be used to leverage relatively large dedications from developments as the city grows. If they fail to do this, then such cities subsequently will have to adopt the much more challenging political strategy of requesting residents to approve bond issues for park land to achieve a given desired level of service."

VERBATIM EXCERPTS - The complete PDF is a 33 full pages long and with annotations at:

https://austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Parks/Parkland_Development/parkland_crompton.pdf

Part 1: Highlights of the Study and Common Problems Encountered

Part 2: Scroll down to "DISCUSSION" for the following information:

- Development Community Objections

- Some in the Development DO Support Increased Parkland Requirements

- Developers Now Use the "Operating and Maintenance Argument"

- Political Case for Parkland Dedication

- Rebuttals to Developer Arguments

- Case Scenario

- Charts

********************

1. What are the sources of the unrealized potential of parkland dedication ordinances?

- Failure to extend ordinances beyond neighborhood parks to embrace community and regional parks

- Failure to extend ordinance requirements into cities’ extraterritorial jurisdictions

- Failure to set dedications at a level that covers all the costs associated with the acquisition and development of the additional park capacity required to meet the demands of new residents

- inability to take advantage of reimbursement provision ordinances

2. Why is their potential not being realized?

- No requirement is included that they be reviewed at regular intervals.

- Developers routinely oppose any expansions of these ordinances and they are a powerful political constituency in many communities. (Rebuttals to the developers’ arguments are provided at the end of this page under "DISCUSSION").

3. Why should elected officials warmly embrace parkland dedication?

- It is fiscally conservative in that those who are benefitting from the service are paying for it; the alternatives are to raise taxes on existing residents or lower the community’s quality of life, neither of which are politically attractive

- A recognition that parkland dedication requirements are not likely to lead to any resident being unable to afford a new home.

These dedications are a means of providing park facilities in newly developed areas of a jurisdiction without burdening existing city residents.

They may be conceptualized as a type of user fee because the intent is that the landowner, developer, or new homeowners, who are responsible for creating the demand for the new park facilities, should pay for the cost of new parks.

Parkland dedication enables (elected officials) to protect the interests of current residents and to manage growth.

in 1984, the Texas Supreme Court concluded in City of College Station vs Turtle Rock Corporation that requiring parkland dedication or fees in lieu “was a valid exercise of the city’s police power because it was substantially related to the health, safety and general welfare of the people.”

The conservative Texas legislature specifically stated in the 1986 legislation: “The term [impact fee] does not include dedication of land for public parks or payment in lieu of the dedication to serve park needs.”

- When fees in lieu of land is appropriate, and based on the fair market value of the land -

(The developer’s portion of the costs may not exceed the amount required for infrastructure improvements that are roughly proportionate to the proposed development.)

- Because most developments are small, only small fragmented spaces would be provided.

- The land dedicated by the developer was likely to be the least suitable for building upon (often drainage ditches, floodplain or detention ponds) and it may also be unsuitable for park use.

- Location of the parkland was determined by the location of the development.

A problem with ordinances that contain only the land and fee in lieu elements is that they provide only for the acquisition of land. The additional capital needed to transform that bare land into a park is borne by existing taxpayers. In some instances, the result is that the dedicated land is never developed into a park and remains sterile open space which detracts from a community’s appeal rather than adding to it. This led 10 Texas communities to expand their ordinances to incorporate a park development fee element to pay for the cost of transforming the land into a park. Thus, the scope of parkland dedication ordinances in Texas has broadened as they have gained legal and public acceptance.

- Different approaches to calculating land values for fees in lieu of parkland -

(cannot be higher than fair market value)

There is widespread recognition that many tax assessors set their appraisals below fair market value in order to avoid the costs associated with large numbers of property owners contesting their valuations.

- McKinney's counter to these “low ball” appraisals, the McKinney ordinance authorizes the city council to upgrade the county assessor’s appraised value if the council elects to do so:

- Rockwall and Haltom City commit to annually revise the fee in lieu amount to reflect changes in land values

- Allen situation exemplifies a common potential problem in that fair market value frequently is presented as a fixed amount per DU (dwelling unit)

- Cities who have a tendency to fix the amount far below fair market value, are unlikely to be challenged by developers

- Denton states: "The value of the land shall be calculated as the average estimated fair market value per acre of the land being subdivided at the time of preliminary plat approval… If the Developer/Owner objects to the fair market value determination, the Developer/Owner at his own expense, may obtain an appraisal by a State of Texas certified real estate appraiser, mutually agreed upon by the City and the Developer/Owner."

- The Colony has 3 options:

a) the most recent appraisal of all or part of the property made by the Central Appraisal District

b) confirmed sale prices of all or part of the property to be developed, or comparable property in close proximity thereof, which have occurred within two 2) years immediately preceding the date of determination

c) Where, in the judgment of the Council, a) or b) above would not, because of changed conditions, be a reliable indication of the then current value of the land being developed, an independent appraisal of the whole property shall be obtained by the City and paid for by the developer

The cities of College Station and Bryan are the only cities whose ordinances provide empirical details as to how their park improvement costs were derived. The derivation for College Station’s neighborhood parks was shown earlier in Table 1.

Cedar Hill, College Station, Flower Mound, and Mansfield authorize developers to construct improvements at a park in lieu of paying the park development fee.

Presumably, the private amenities will absorb some of the demand generated by the new homes that would otherwise have had to be accommodated by public parks. (However, little or no guidance was given on how to determine how much credit should be allowed - including up to a maximum of 50 percent...which introduces an element of arbitrariness that could result in similar developments being treated differently..)

Whenever credit is given for private amenities, the ordinances invariably include requirements that ensure a stable source of funding is available to maintain and renovate the facilities.

The “rough proportionality” requirement mandates that proportionate credit be given for private amenities. Private park space cannot be considered part of a community’s existing level of service. Thus, such credit does reduce the amount of public open space. This has a marked adverse effect on the formula for calculating dedication requirements.

Reimbursement Clause

When sufficient cash accrues from these fee in lieu of parkland payments, the city attempts to purchase adequate land for a park. Unfortunately, by the time enough money has been paid by developments to accomplish this, most of the land suitable for a park of appropriate size is likely to have been acquired for development. Invariably, the only land available for a park is floodplain or detention basin land that developers could not use, but which is also often inferior for use as a park. Alternatively, if potentially good park land is still available, the cost of its acquisition is likely to be relatively high since land prices are likely to rise as intensity of development in an area increases.

Negotiation with landowners at times when activity in the real-estate market is slow, when a bargain sale opportunity becomes available, or when the land is beyond the community’s existing developed areas, can result in good park and recreational land being purchased at a relatively low price. It is also likely to be easier to acquire substantial tracts of 50 to 300 acres, for example, at this time than after development extends to these outlying areas. In effect, these acquisitions represent excess capacity to the community’s current needs. Adopting this approach is likely to be supported by developers, because the existence of parks makes new developments more attractive to homeowners.

"Nexus Rule" confirmed by U.S. Supreme Court in Nollan vs California Coastal Commission (483 U.S. 825.1987). This means that an agency should have a parks master plan that divides the jurisdiction into geographical districts. Each district should have a separate fund in which to credit all dedication fees in lieu and park development fees originating from that district. These revenues should be spent on parks within the district in which they originated. The size of these districts is determined by the distance that residents are likely to travel to visit a park.

Time Limitation for Expending Fees in Lieu

The courts have made it clear that when fees in lieu are paid, there is an expectation that the homes generating them will benefit from new park amenities within a reasonable timeframe.

- The five-year timeframe adopted by, for example, College Station, Cedar Park, and Austin, probably reflects the rapid population growth occurring in these communities. It is surely unrealistic, even in rapid growth communities, that shorter timeframes of two or three years are sufficient to collect funds, identify and acquire available park land, and to let contracts to develop a park. For many communities, it seems likely that an eight- or 10-year timeframe is required to accomplish these tasks. If the reasonable timeframe criterion is not met, then ordinances have to provide for those who pay the fees in lieu to receive a refund. (Explanations are provided as to why the likelihood of refunds being requested is minimal)

The Scope And Range Of Texas Cities’ Parkland Dedication Ordinances

While municipalities in other states were broadening the mandate of exactions, “The exception to this trend is in the state of Texas, where municipalities predominantly restrict their use of the funds to neighborhood parks”. This view of the legitimacy of a broader spectrum of parks being eligible for dedication fees was reinforced over a decade ago by the National Recreation and Park Association in its guidelines for planners. Although most cities’ enabling legislation gave them a mandate to require dedication for more than neighborhood parks, it should be noted that tradition, inertia, and presumably opposition from the development community, in many cases confined their implementation of dedication only to neighborhood parks.

1. Non-residential Park Land Dedications: (Colleyville, Hutto, and Southlake as examples)

2. Extra Territorial Jurisdictions (Austin as an example)

Timeframe for Revising Ordinances

In only 11 of the 48 ordinances reviewed is a timeframe for reviewing the ordinance incorporated. College Station (similarly Bryan, League City, and Plano): "review the Fees established and amount of land dedication required at least once every three (3) years.” In Wylie it is every two years; while in San Antonio and Arlington the review period is every five years. There were five communities in which revisions to fees in lieu are integrated into the annual budget process: Angleton, Haltom, Pflugerville, Rockwell, and Southlake.

Criteria for Acceptance of Parkland: Minimum Size and Floodplain/Detention Area

- Minimum Size

Most ordinances (37 of the 48) specify a preferred minimum size for dedicated parkland, recognizing that very small parks provide limited scope for providing amenities and are relatively expensive to maintain in terms of cost per user served. Preferences range from ¼ acre in League City to 10 acres in McKinney, Rockwall and Sugarland, with the most frequent preferred minimum size being 5 acres (n = 15). It is emphasized that these are desired minimums and none of the ordinances categorically reject the possibility of accepting land dedications that are lower than their preference. The New Braunfels ordinance is typical: The City Council and the New Braunfels Parks and Recreation Department generally consider that development of an area less than five acres for neighborhood park purposes may be inefficient for public maintenance.

- Floodplain and Detention Pond Land (examples)

College Station ordinance states, “Land in floodplains or designated greenways will be considered on a three-for-one basis. Three acres of floodplain or greenway will be equal to one acre of park land.” Four additional communities adopted this three-to-one ratio and six specify a 2:1 ratio. The Mansfield ordinance states: The City "shall not accept land ... within floodplain and floodway designated areas … unless individually and expressly approved by the Director." The League City ordinance is unequivocal in rejecting as “unsuitable” any area located in the 100-year floodplain but “an exception may be a ballfield that is located in a day detention basin with the approval of the Parks Board and City Council.” The Bryan ordinance states: Consideration will be given to land that is in the floodplain … as long as … it is suitable for park improvements. San Antonio offers the most specific and comprehensive regulations for acceptance of detention areas.

------------------------------------DISCUSSION-------------------------------------

When initiating dedication ordinances, city councils often seek to appease vigorous opposition from the development community by setting unrealistically low dedication requirements. They may rationalize that it is an accomplishment to get such an ordinance passed and “some revenue is better than no revenue.” The lack of empirical procedures in subsequent reviews of the dedication requirement makes it vulnerable to incrementalism.

Invariably, they fail to cover the costs associated with acquisition of additional park capacity created by additional demand from new homeowners.

DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY OBJECTIONS

The lack of regular review may explain the legal weaknesses manifested in many of the ordinances. There simply has been no reason to re-examine and update them to be consistent with contemporary best practice and court guidelines. Given these legal weaknesses, it is significant that there has been no substantive litigation initiated by the development community in Texas challenging parkland dedication ordinances in the 25 years that have passed since the Turtle Rock case in 1984. This suggests the nominal magnitude of most of the ordinances is so small in the context of the total cost of a development that it is not worthwhile for developers to legally challenge them.

Developers are very conscious of the Fifth Amendment “takings” issue. Although the courts have ruled that parkland dedication does not constitute a taking of private land without adequate compensation, many Texas developers resent the courts’ interpretations. They view it as an intrusion of their right to use all of their land as they see fit and find the principle of park land dedication to be repulsive and an anathema. It is this perspective that results in discussions of dedication issues with developers often being highly emotional. In some contexts, animosity from developers may be perceived by some elected officials to endanger their personal political aspirations, because developers and real estate interests are influential in many Texas communities and are major contributors to local election campaigns. Indeed, some elected officials are involved in real estate or associated professions, and oppose substantive dedications because they are antithetical to their professional value systems. In many Texas communities, residential development has not been expected to pay its own way in the past. The contention that growth should pay for itself is a relatively recent interjection into Texas’s political discourse.

REASONS WHY SOME IN THE DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY

SUPPORT THE INCREASED DEDICATION OF PARKLAND

- Parkland dedications make parks available at the time, or soon after, new homeowners move into a development. This enhances the property’s salability. Many real estate projects prominently feature recreation amenities in their promotional campaigns.

- They may recognize that ensuring a given level of park provision throughout a community contributes to its general quality of life.

- A growing recognition among Texas residents that in the absence of dedication and impact fees for an array of new facilities, new development is likely to result in local tax increases or in cutbacks in the prevailing level of service. In these contexts, the challenge of growth advocates is to demonstrate that their projects will not have an adverse fiscal impact on the community.

- Some factions in a community invariably view developers with distrust and suspicion. Endorsement of a substantive parkland dedication ordinance may contribute to alleviating this negative image.

In contrast to the vociferous opposition typically expressed by developers, few among the general public are likely to engage in the debate. They have little awareness or understanding of parkland dedication ordinances and do not recognize that they will be adversely impacted if they are merely nominal, so there generally is a lack of a proordinance constituency to counter opposition from the development community. A strategy for reducing this imbalance among constituencies is to make the opportunity costs tangible, pointing out to the general public the cost of not increasing the ordinance requirements.

DEVELOPERS NOW UTILIZE THE EMERGING "O&M ARGUMENT"

As their traditional arguments against parkland dedication requirements have encountered more resistance, some in the development community have embraced a new line of attack: How can you justify building new parks when you are struggling to find the money to properly maintain and operate those that the city already owns?

FOUR REBUTTALS TO THE "O&M ARGUMENT"

1. Allocation of operation and maintenance funds is part of the annual budget process. As such, it reflects a short-term view of economic conditions that prevail in the city at that time. In contrast, parkland dedication is a one-time, major investment in capital infrastructure that reflects a long-term view of amenities the city should have in the future. If a current council decides not to construct new parks, then it has pre-empted the right of future residents to have them, because there will be no land available to retrospectively construct them. A current council has an obligation not to pre-empt the options of future councils. Not to proceed with a parkland dedication ordinance because of concerns about future operation and maintenance costs would be myopic and arrogant since the future ability to meet such costs is unknown. Previous councils had sufficient vision to create the opportunities a community currently enjoys. If a current council does not continue to make the same opportunities available to future generations, they would be lacking vision.

2. Amenities that are not on the tax rolls in a community create much of the value of properties that are on the tax rolls. Such amenities would include parks, schools, roads, churches, street spaces, nonprofit arts facilities, police and fire facilities and services, et al. Specifically in the case of parks, the real estate market consistently demonstrates that many people are willing to pay a larger amount for property located close to parks and open-space areas. The higher value of these residences means that their owners pay higher property taxes. In many instances, if the incremental amount of taxes paid by each property which is attributable to the presence of a nearby park is aggregated, it will be sufficient to pay the annual costs of operating and maintaining the park (Crompton, 2004).

3. Costs can be minimized by focusing only on natural parks. Cost of operations is higher for those parks containing elements such as athletic fields. If a park is designed at the outset with minimal maintenance costs in mind, then that can be accomplished.

4. The empirical evidence in the past two decades overwhelmingly reports that while residential development may generate significant tax revenue, the cost of providing public services and infrastructure to that development is likely to exceed the tax revenue emanating from it. Thus, preserving open space and creating parks can be less expensive alternatives to development. Indeed, some communities have elected to acquire park and open-space land, rather than allow it to be used for residential development, because this reduces the net deficit for their residents which would occur if new homes were built on that land.

THE POLITICAL CASE FOR PARKLAND DEDICATION

1. A bedrock principle of fiscal conservation is the Benefit Principle, which states that those who benefit from government services should pay for them.

2. Elected officials can respond to infrastructure and amenity needs created by new growth in one of three ways:

a) Request existing residents to pay the bills by approving the issuance of general obligation bonds that will raise their taxes. Many residents are likely to ask, “Why should we agree to raise our property taxes to build parks many miles away from where we live that we will never use?”

b) Decline to provide the new infrastructure and amenities or provide them at a lower level of service than prevails elsewhere in the community. In effect, this means accepting a reduction in the community’s quality of life.

c) Require new development to pay the cost of providing the infrastructure and amenities the need for which has been created by them. Few elected officials are likely to run for office on a platform of raising the taxes of existing residents (option 1) or lowering a community’s quality of life (option 2). Indeed, if a public referendum were held inviting the public to vote on which option they would prefer, the likely result would be overwhelming support for option 3.

3. It would "appear" that the dedication requirement will lead to some potential home buyers being priced out of the market. The development community is likely to vigorously promote this position. The reality of parkland dedication requirements is that they are not likely to lead to any increase in the price of a new home. The new parkland dedication fee could be absorbed in one of three ways.

a) Passing it through to the home buyer

b) Absorbed by the developer. This is not a viable option, because a developer’s willingness to accept the level of financial risk associated with a project is predicated on a given projected profit margin

c) The non-feasibility of options (1) and (2) mean that the only viable option for absorbing the additional $1.000 dedication fee is to reduce the developer’s costs. This can be done in one of three ways:

1. Reduce the house size by 10 square feet

2. Engage in “value engineering” to reduce the costs of finishes, fittings, furnishings or landscaping in the house by $1,000.

3. Pay less for the land. The imposition of a $1,000 parkland dedication fee effectively changes market forces and reduces the value of the land to be sold. This is explained in the following scenario:

Suppose a developer is about to purchase a piece of land when the city announces a $1,000 increase in the park dedication requirement. Before the increase, the developer could build 100 units on the land and sell them for $150,000 each. Based upon the cost of construction and required profit, she was willing to pay $2 million for the land. As a result of the new ordinance, the developer concludes she now has to charge $151,000 per unit due to the increased cost. However, if the developer can now sell the houses for $151,000 each, why did she not charge that price before the imposition of the fee? In fact, the market for comparable housing limits her to selling the houses for $150,000 each; thus, she will not be able to sell them for $151,000. As a result, the builder is only willing to pay $1.9 million for the land, so she is able to reduce costs and maintain her profit margin (i.e., $2 million [100 lots x $1,000]).

4. If taxes are raised to meet the costs of new parks, then the assessed property values of existing homes will be effectively reduced since potential buyers are likely to pay less for a property with a higher tax burden.

The limited use of parkland dedication in Texas is surprising given its legal validation, the expansion of its scope that has been accepted by the courts, and its ability to shift the tax burden of maintaining existing service levels away from existing residents to those new residents who create the need for additional amenities. This analysis of Texas ordinances suggests recognition of these appealing political realities remains limited in Texas. Clearly, there is considerable scope for both extending parkland dedication to municipalities that do not have such an ordinance, and increasing the requirements in those cities which currently have an ordinance.

In most communities, parkland dedication ordinances are under the purview of planning departments since they constitute a component of a city’s subdivision regulations. The limitations and failings of ordinances described in this paper suggest that many park and recreation directors have not taken a proactive role in the development of these ordinances.

This is unfortunate given that many agencies are struggling to find resources to expand and/or renovate their park systems. Parkland dedication ordinances offer a mechanism for doing this, but the field’s leaders in a community must be centrally involved in advocating for the improvement and enhancement of these ordinances if their great potential is to be realized.

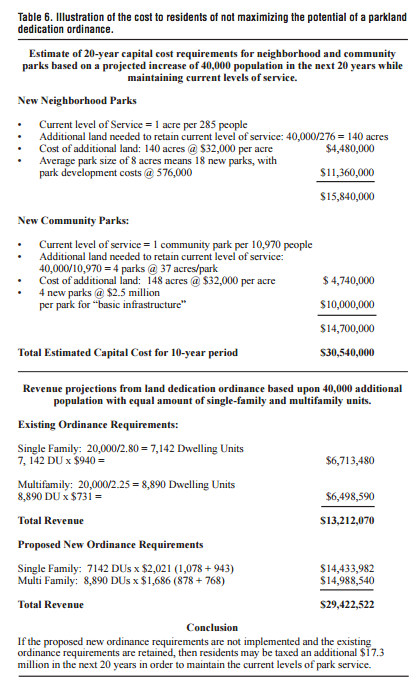

---CHARTS---